|

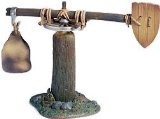

A quintain is a sort of inanimate target for jousting, especially for training, but sometimes for recreational games (see “The Rise of the Joust” in Tournament ). Quintains are also sometimes used in water jousting. ). Quintains are also sometimes used in water jousting.

Strutt has a lengthy section on quintains in his Sports and Pastimes of the people of England; this article from The Saturday Magazine describes quintains from “England in the Olden Time” for its readers in 1839. There is also Une redevance Ludique: La quintaine «gothique» des nouveaux maries et des arisans” in Les jeux à la Renaissance . .

I've included some contemporary descriptions in addition to the links to images below. While the images are useful for understanding the shape and form of a quintain, the descriptions go further to discuss how they were made, and on what sorts of occasions they were used.

- “So he went on his way toward England and, when in the week of Pentecost he came to Arras and was lodged on the market-place, there was a great stir in the city. For Philip, Count of Flanders, being then in the city, caused a quintain to be set up in the market-place, a great square in the midst of the town; now a quintain is a strong shield hung securely to a beam, whereon aspirants for knighthood and stalwart youths mounted on galloping chargers may try their strength by breaking their lances or piercing the obstacle – a prelude this to the exercises of knighthood. And Giraldus, who looked on from a lofty gallery in his lodgings (and would that he had been able to look down upon their sport as mere vanity!) saw the Count himself, and with him such a multitude of noble knights and barons, so many a fine horse galloping at the shield and so many lances broken, that, though he diligently watched each several thing, he could not sufficiently wonder at the whole. But when the sport had lasted about an hour and all that great space had been filled with such a throng of nobles, the Count suddenly departed, all his companions dispersed, and where a little while ago such pomp was visible, now neither man nor beast was to be seen nor aught save the marketplace utterly deserted. Which in truth is a clear proof, as Giraldus himself is wont to say of these things, and their like, that all things under the sun are subject unto vanity and, as it were, phantasms swiftly passing away, and that all the things of this world endure but for a moment and are gone.”

De rebus a se gestis, Chapter 4, in The Autobiography of Gerald of Wales (trans. H.E. Butler), 1177 (trans. H.E. Butler), 1177

- Chapters XXX and XXXI of Raoul de Cambrai, 12th-13th century (especially the description of the quintain at ll. 606-607: “Une quintaine drecent la fors et preiz / De .ij. escus, de .ij. haubers safrez”); see pp. 142-144 of the Internet Archive edition, or pp. 9-10 of the Jessie Crosland translation.

- Banin wins at the quintain, Lancelot du Lac (BNF Fr. 344, fol. 207v), third quarter of the 13th century

- “At this time, also, that is to say in the first fortnight of Lent [in 1253], the king on a slight occasion compelled the citizens of London (whom we usually call barons, owing to the dignity of their city, and the ancient liberty of its citizens) to contribute the sum of a thousand marks. At the same time, too, the young men of London tested their own powers, and the speed of their horses, in the game which si commonly called “Quintain,” having fixed on a peacock as the prize in the sport. Some attendants and pages of the king’s household (he being then at Westminster), were indignant at this, and insulted the citizens, calling them rustics, scurvy and soapy wrteches, and at once entered the lists to oppose them. The Londoners eagerly accepted their challenge, and after beating their backs with the broke npiek handlse till they became black and blue, they hurled all the royal attendants from their horses, or put them to flight. The fugitives then went ot the king, and with clasped hands and gushing tears besought him no to let such a great offence pass unpunished; and he, resorting to his usual kind of vengeance, extorted a large sum of money from the citizens.

Matthew Paris's English History (trans. Rev. J.A. Giles)

- Knights jousting, Histoire de Merlin (BNF Fr. 95, fol. 273), c. 1280-1290

- An ape tilts at a quintain, psalter (Douce 5, fol. 36r), c. 1320-1330

- BNF Fr. 17000, second quarter of the 14th century: Marques at the quintain (fol. 11) and Helcanus and Josias at the quintaine (fol. 263)

- Marques at the quintain, Marques de Rome (BNF Fr. 22548, fol. 24), second quarter of the 14th century

- Boys jousting, The Romance of Alexander (Bodley 264, fol. 82v), c. 1338-44; a barrel on a pole appears to be used as a quintain on fol. 56r

- A knight at the quintain from a 14th century psalter

- A 15th century illustration of a quintain

- From Merlin, by Herry Lovelich, c. 1450:

“Thus the covenaunt was fenyssched there, / be-twene the kyng and Merlyn jn fere. / Gret joye maden they jn that cyte / of here kyng so 3ong jn his degre, / that so worthy a man of armes he was, / and thereto so hardy jn eche a plas. / so that for joye of that solempnite / the worhty Burgeys of that cyte / a qwyntyn tehy reryd there besyde / jn a fayr medewe that jlke tyde, / the 3onge knyhtes to bowrdeyen there / with scheldes hangeng abowten here swere. / This revel lasted fully viij dayes / with grete feste, as this storye sayes.” ll. 8741-8754)

“Aftyr noon was vpe set the qwyntyn, / the 3onge knytes þere justed wel and fyn, / and Boordeieden there alle theke day, / and aftyrward to torneyeng, with-outen nay.” (ll. 9337-9340)

- From The Prose Merlin, c. 1450-1460:

“And whan the caroles hadde longe dured, the ladyes and the maydenys satte down vpon the grene herbes nad fressh floures, and the squyres set vp a quyntayne in the myddes of the medowes, and wente to bourde a partye of the yonge knygthes, and on that other parte bourded the yonge squyres with sheldes oon a-gein a-nother that neuer ne lefte till euesonge tyme.” (p. 310)

“Whan these children were thus a-dubbed, than eche of hem a-dubbed soche companye as thei wolde lede of soche as thei hadde brought with hem; and whan thei were alle redy thei wente to high messe, that the archebisshop sange, and whan masse was don thei com a-gein to the paleise to mete, and ther helde Arthur grete court and grete feste, and it nedith not to speke of the meesse ne the seruise that thei hadde that day, for it were but losse of tyme; and after mete wolde these yonge bachelers haue reised a quyntayn in the medowes, but the kynge hem diffended by the counseile of Merlin, for that the contrey was so trouble and full of werre, and the cristin sore turmented with saisnes that were entred in the londe.” (p. 375, c. 1450-1460)

- “After mete was the quyntayne reysed, and therat bourded the yonge bachelers.”

The Grand Tournament at Logres, Prose Merlin

- 1547 Jeu de la Quintaine, a description of the games celebrating the coronation of Henri II of France

Can I not say, I thanke you? My better parts Are all throwne downe, and that which here stands vp Is but a quintine, a meere liuelesse blocke. As You Like It (ll. 415-417) - “The marching forth of citizens’ sons, and other young men on horseback, with disarmed lances and shields, there to practise feats of war, man against man, hath long since been left off, but in their stead they have used on horseback to run at a dead mark, called a quintain … This exercise of running at the quintain was practised by the youthful citizens as well in summer as in winter, namely, in the feast of Christmas, I have seen a quintain set upon Cornhill, by the Leadenhall, where the attendants on the lords of merry disports have run, and made great pastime; for he that hit not hte broad end of the quintain was of all men laughed to scorn, and he that hit it full, if he rid not the faster, had a sound blow in his neck with a bag full of sand hung on the other end.”

A Survay of London by John Stowe, 1598 (see also Of sports and pastimes in this Citie in the 1603 edition, which includes a small illustration of a quintain)

- Joust at the Quintain by Stradanus, 1555

“Quintain” can also refer to a sort of balance-game, as described on Katherine Kerr’s website. (I haven't heard a medieval description that uses the term, though Strutt mentions it; he calls it “the living quintain” or “the human quintain.”)

- Bas-de-page illustrations on fols. 43v and 69v, the Rutland Psalter (British Library Additional 62925), c. 1260

- Bas-de-page, the Queen Mary Psalter (Brit. Lib. Royal 2 B VII, fol. 162r), c. 1310-1320

- Bas-de-page, Luttrell Psalter (Brit. Lib. Add. 42130, fol. 152v), c. 1325-1340

- Bas-de-page, The Romance of Alexander (Bodley 264, fol. 100r), c. 1338-44

- Bas-de-page from a psalter (PML M.88, fol. 178r), c. 1370-1380

- Bas-de-page from an Annunciation in a 14th century psalter (Musée Condé 64, fol. 25r)

- Monkeys in a bas-de-page, the Pontifical of Guillaum Durand (Bibl. Sainte-Geneviève 143, fol. 1), before 1390

- An Alsatian tapestry, late 14th century

- An ivory comb made in France, c. 1490-1500

- A stained glass roundel, c. 1500

- Bas-de-page illustrations on fols. 35v and 41v, a book of hours (Douce 276), beginning of the 16th century

|